What do Contingent Fee Lawyers Consider when Evaluating Novelty and Non-Obviousness?

As discussed in my prior post, What do Contingent Fee Lawyers Look for When Considering Validity During Due Diligence?, patent lawyers must consider the question of novelty and obviousness under 35 USC 102 and 35 USC 103 when considering a case on a contingent fee basis.

Of these two areas, anticipation is rarely a dispositive factor later during a contingent fee licensing program. Typically the more significant issue becomes combinations of art with "expert" arguments that "it would have been obvious" to come up with the invention. However, with knowledge of the law, inventors can take action to establish a factual record for non-obviousness throughout the inventive process when the truth is most accessible without hindsight bias.

In this post, I will first discuss anticipation under 35 USC 102. Then, I will address obviousness under 35 USC 103 and factors that should be considered by inventors and patent owners as they document their inventive process.

Novelty (35 USC 102)

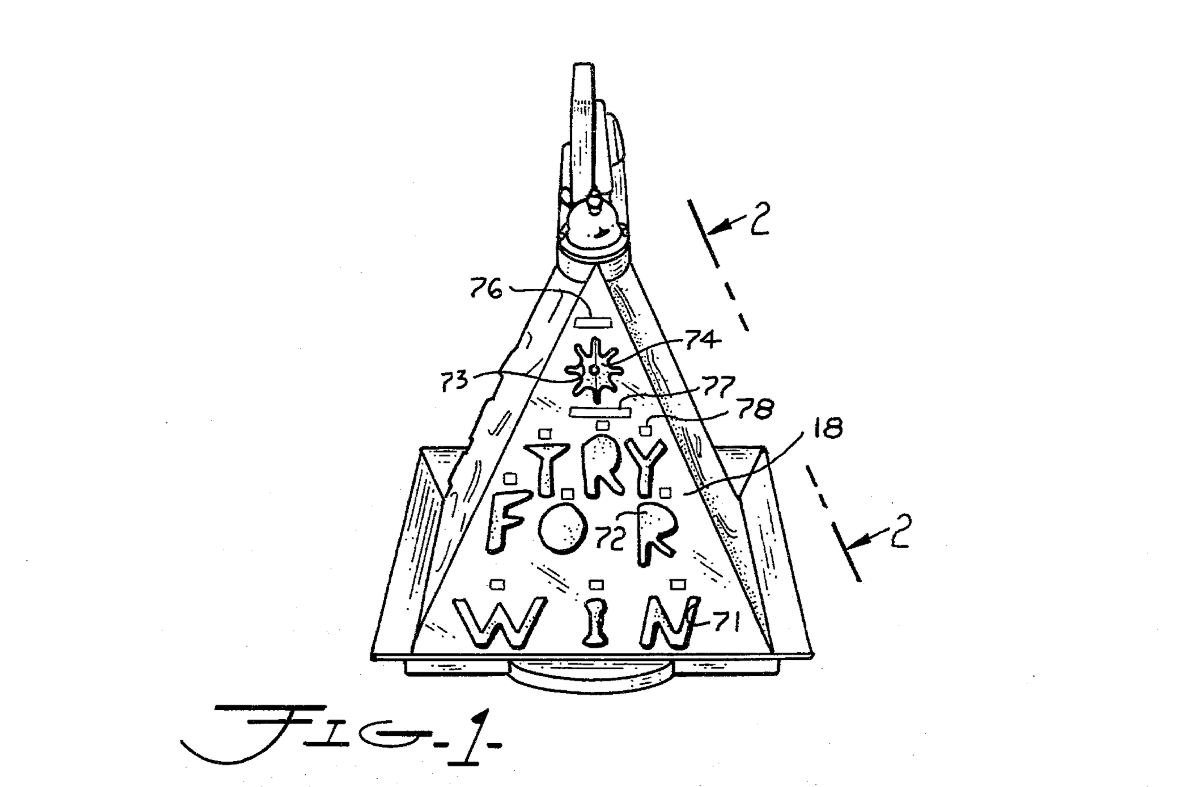

Novelty under 35 USC 102 essentially requires that the inventor came up with something "new." In other words, the invention cannot be "anticipated" by an art reference that was previously publicly available. If a claim is anticipated, then each element of the claim is shown in a prior reference.

For good patent claims, it is relatively hard to show anticipation. On occasion, there is a reference that might explicitly disclose most elements but does not disclose others. An examiner may argue that the reference "inherently" discloses and therefore anticipates the invention; however, showing inherent anticipation requires rationale or evidence. See MPEP 2112.

During the patent examination process, it is common to see rejections under 35 USC 102. In responses, an applicant can:

argue the cited art does not "anticipate" the claim as filed by describing the shortcomings of the art relative to the claim, or

amend the claim to differentiate it from the art.

If amendments are made to preserve validity, however, it can limit the scope of the claims and the extent of possible infringement.

For a contingent fee case, we will look at the file wrapper to determine the extent to which art has been cited, and the "closeness" of the cited art to the claimed invention. We will also look to see if there have been any concessions to the scope of the claims made during prosecution relative to the alleged infringement. To the extent there are meaningful differences between the known art and no concessions to the scope of the claims that would preclude the alleged infringement, we will consider the issue of obviousness.

Obviousness (35 USC 103)

Non-Obviousness under 35 USC 103 is a more subjective analysis. The invention cannot be "obvious" given what was known to a "person of ordinary skill in the art at the time of the invention." This standard has been defined over the years with Graham v. John Deere Co., 383 U.S. 1, 148 USPQ 459 (1966) and its progeny including KSR International Co. v. Teleflex Inc. (KSR), 550 U.S. 398, 82 USPQ2d 1385 (2007). See also MPEP 2141, which summarizes the high-level test (emphasis added):

Obviousness is a question of law based on underlying factual inquiries. The factual inquiries enunciated by the Court are as follows:

(A) Determining the scope and content of the prior art;

(B) Ascertaining the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art; and

(C) Resolving the level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art.

Objective evidence relevant to the issue of obviousness must be evaluated by Office personnel. Id. at 17-18, 148 USPQ at 467. Such evidence, sometimes referred to as “secondary considerations,” may include evidence of commercial success, long-felt but unsolved needs, failure of others, and unexpected results. The evidence may be included in the specification as filed, accompany the application on filing, or be provided in a timely manner at some other point during the prosecution. The weight to be given any objective evidence is made on a case-by-case basis. The mere fact that an applicant has presented evidence does not mean that the evidence is dispositive of the issue of obviousness.

During the patent examination process, obviousness rejections are also commonly made. Furthermore, these types of obviousness arguments are more commonly made by patent challengers than "anticipation" arguments.

Challengers often attempt to invalidate patents using a large number of combinations of art with arguments that it would have been obvious to piece the references together at the time of the invention. To "win," the patent owner needs to be able to show each asserted combination fails to show obviousness; the challenger only needs to prove one combination shows obviousness.

Due to the importance of defending obviousness-type invalidity arguments after patent issuance, when considering a contingent fee case, we will look strongly at the possibility of success from this type of attack on patent validity. To assist with this review process and improve their case, inventors and patent owners should do everything they can to establish objective evidence of non-obviousness throughout the inventive process and the development of the market. Compiling this type of evidence over time is very important. “[E]vidence [of secondary considerations] is ‘secondary’ in time does not mean that it is secondary in importance.” See, e.g., Truswall Sys. Corp. v. Hydro-Air Engineering, Inc., 813 F.2d 1207, 1212 (Fed. Cir. 1987).

In my next post, I will discuss the objective evidence of non-obviousness further and provide additional examples of this type of proof from "famous" cases. Inventors and patent owners should actively compile this type of relevant information throughout the life of their patents to help combat “obviousness” arguments.