In my prior articles, I have discussed substantially copying claims, and third-party submissions. This raises the question, should you copy competitors claims, or file a Third-Party Submission (3PS) (if the timing requirements of 35 USC 122(e)(1) are met)? Deep neural network techniques can be utilized to help decide the best course of action.

All in Patent Prosecution

Using Deep Neural Networks to Seed Forward Citations with Third-Party Submissions

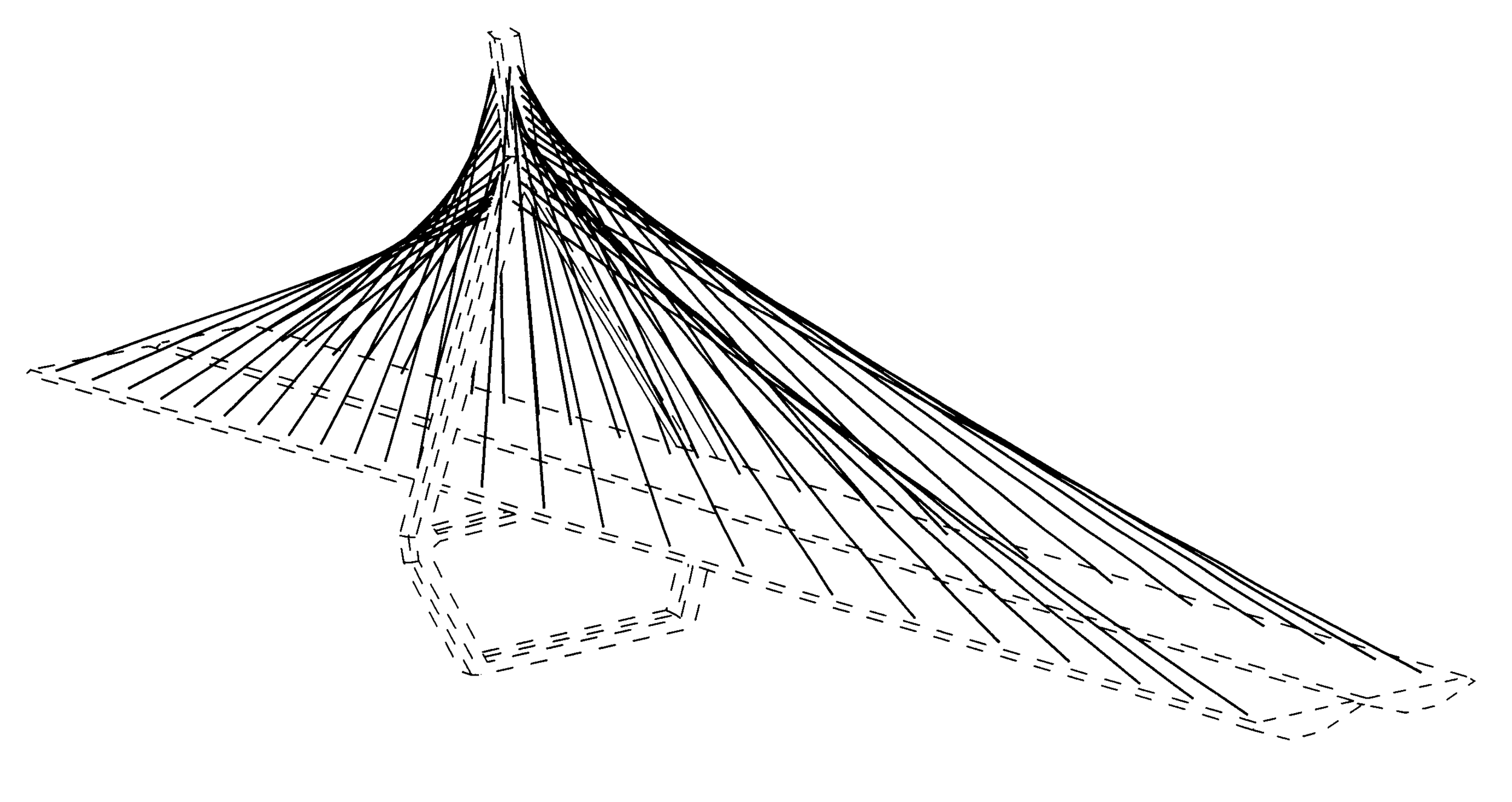

Forward patent citations of your specification can make your patent more valuable. Deep neural networks can be used to help patent owners increase their forward citation count through the use of Third-Party Submission (3PS) forms in their competitors patent applications. Based on the information discovered and generated using deep neural network techniques, a 3PS form can be completed and submitted in the third-party application. In time, the patent owner’s application will then show an increased forward citation count based on that submission.

Using Deep Neural Networks to Mine Your Patent Specification for Claims that Your Competitors Want

In my article, “Finding Forward Citations and Getting Claims Your Competitors Want Using Continuations,” I discuss the concept of obtaining claims that your competitors are seeking to obtain and that your patent specification pre-dates and supports. In that article, the prerequisite to doing this was finding a forward citation to your patent where it was used to block the competitor. Wouldn’t it be nice if you could automate the discovery of competitor claims that read on to your prior patent specifications, even if an Examiner hasn’t appreciated this fact? This can be done using deep neural network sentence encoders.

Using Deep Neural Networks to Strengthen Your Information Disclosure Statement Submissions

With more comprehensive art citations during prosecution, a patent will be more likely withstand attacks under 35 USC 102 and 35 USC 103. This benefit to the validity of a patent can be maximized when the most relevant portions of each cited reference are made of record and presented to the Examiner for consideration. With deep neural network sentence encoders, highly detailed and relevant pin citations for each art reference can be mapped to each claim element sought during prosecution and provided to the Examiner for consideration. Any resulting patent will be immunized against attack from these or similar references.

Using Deep Neural Networks to Streamline Patent Prosecution and Litigation Tasks

Patent prosecution and litigation tasks can be streamlined and improved using deep neural networks trained to determine semantic similarity between sentences. In the next series of articles, I will discuss using this type of sentence encoder deep neural network for various patent related tasks including.

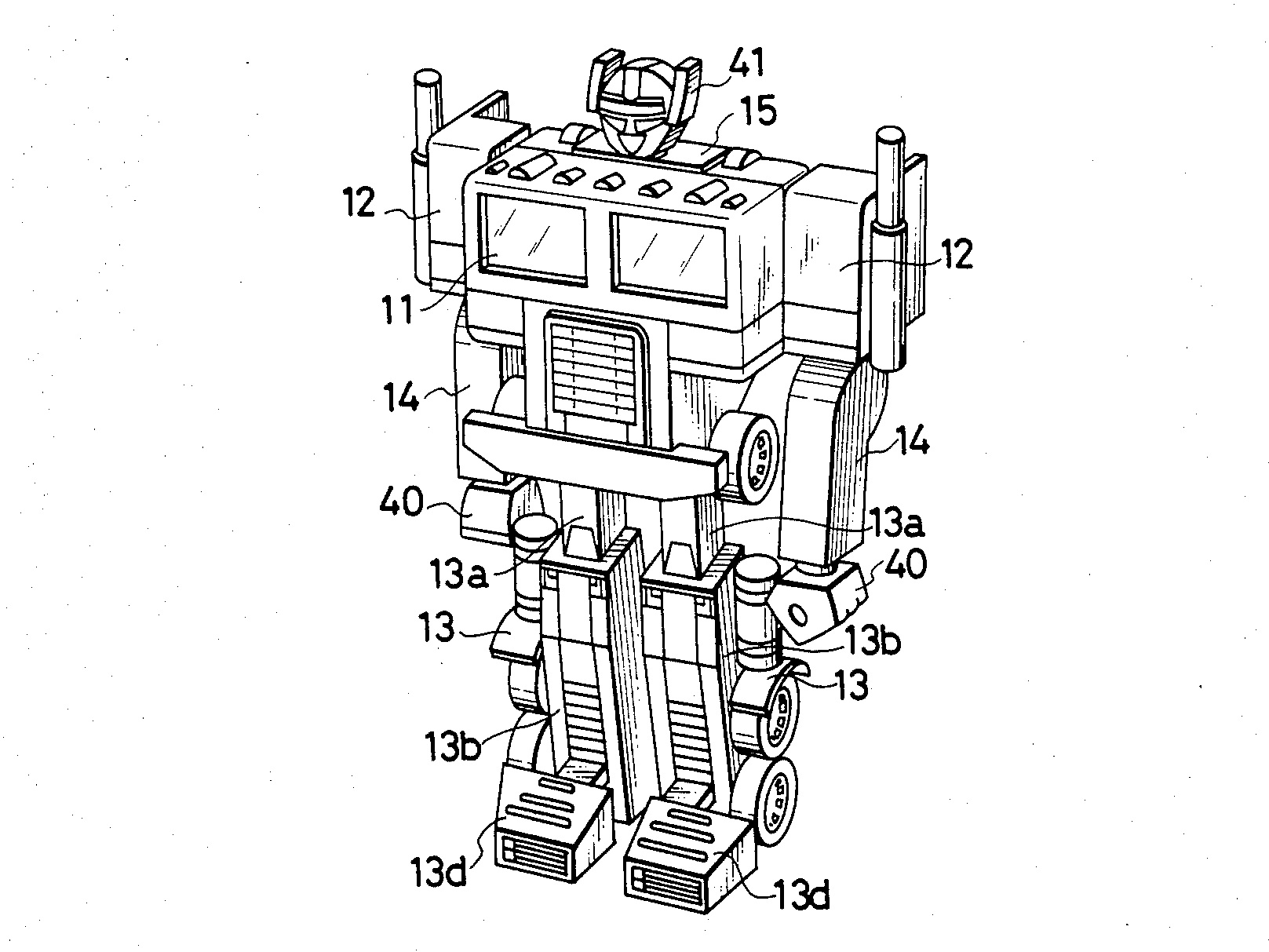

Mining the Patent Specification for Infringement Using Continuations

As patent portfolios age, the core concept of the original claims can be used as a framework for later claims to track what competitors are doing. Using continuations, the core concept of the claims can be modified by broadening (removing aspects from the claims) and narrowing the claims (using the additional disclosure that was not initially the focus of claims in earlier patents). By doing this, numerous patents and claims of different scope can be drafted over time that are tailored to exactly what your competitors are doing. This can turn a single patent into a formidable patent portfolio that can be difficult and very expensive for your competitors to prevail against.

Finding Forward Citations and Getting Claims Your Competitors Want Using Continuations

With a pending continuation, a patent owner is able to monitor and act on forward citations that surface over time. Forward citations are instances where later filed patent applications cite back to your patent specification. This is similar to a journal article citing to prior journal articles that are relevant or otherwise used for background information. If your patent is a forward citation and is cited as a 102 reference it means that a patent examiner has specifically determined that your patent is a "blocking patent" to the claims sought by the later applicant. This is powerful and actionable information.

Before Your Patent Issues, File a Continuation!

Given that the first application only covers what is specifically called out in the Claims, it is my strong opinion that a continuation should be filed before the issuance of the patent to protect additional material not encompassed by the first set of Claims. A continuation is essentially a copy of the non-provisional application, that claims the benefit of the provisional and prior non-provisional applications. The continuation also contains new patent Claims. The continuation allows an inventor to continue to claim other inventions in the disclosure with the filing date of the original provisional application.

Converting a Provisional to a Non-Provisional Application to Obtain Your First Issued Patent

With the provisional on file, an inventor will have a year to convert the provisional application to a “non-provisional” application. This could occur any time during the year after filing the non-provisional, but the sooner the conversion to a non-provisional occurs the less likely issues will arise due to third-party filings within the year period.

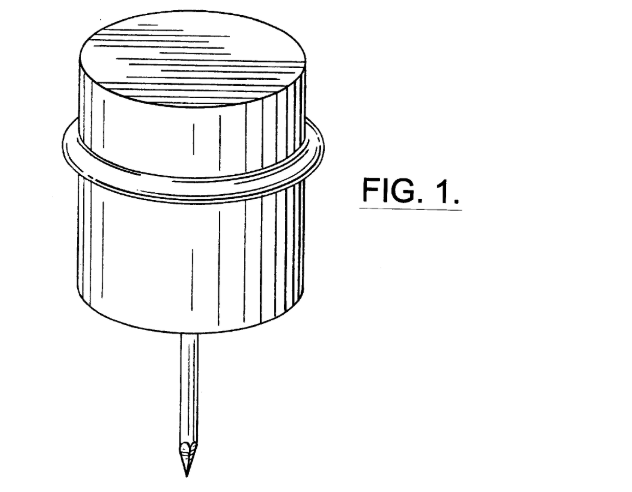

Starting The Patent Process with a Comprehensive Design Patent Application

Provisional patent applications cannot be converted into design patent applications. Thus, another form of protection an inventor should consider early in the patent process is whether design patent protection would be appropriate for any of its intellectual property. Design patents cover visual ornamental characteristics of an article of manufacture. For example, this could apply to the visual design of a product (or portion thereof) or mobile application user interfaces.

Starting The Patent Process with a Detailed Provisional Patent Application

Given that the patent system is now a “first to file” system, a comprehensive provisional patent (or series of provisional patents) may be the best first step for starting to protect the IP for an inventor, a startup or new product at an established company, because it can be done relatively quickly and then converted into a full non-provisional filing.

Proactive Patent Prosecution

When an inventor starts down the path of obtaining patent protection, it is important to understand that the process does not end with an issued patent. Unless superficial protection is desired (e.g., a piece of paper to hang on the wall), patenting an invention is an ongoing process. Inventors should keep at least one application in the patent portfolio pending at all times. When the portfolio is pending, it can adapt as an offensive and defensive tool as the market for the technology evolves. I call this ongoing process “proactive patent prosecution.”

What is a Patent Specification Support Chart?

A specification support chart is a two column chart with each element of the claim language in the left column, and the corresponding specification support from the specification and figures as filed in the right hand column.

What do Contingent Fee Lawyers Look for When Considering Specification Based Defenses?

The best contingent fee case will have many issued Patent claims, but among them, there should be a narrowly crafted claim with clear language that corresponds directly with the alleged infringement. The best "contingent fee" claims will also be unquestionably supported and enabled by the specification and be free of "means plus function" language.

Making Sense of the Mess Caused by Alice, and Evaluating a Contingent Fee Patent Matter for Subject Matter Eligibility

It used to be that the law surrounding subject matter eligibility was clear-cut and well established. The Supreme Court's “Alice” decision has cast a shadow over the application of 35 USC 101. We discuss one way to make sense of the current case law. For now, patent owners should analyze the current law to outline, identify, and amplify the aspects of their invention that are not “abstract” or indicate an “inventive concept” such as new technological improvements and/or unconventional features that go against what has been done before.

How Do You Cite to a YouTube Video as Non-Patent Literature in an Information Disclosure Statement?

YouTube is a fantastic source of information. There is seemingly a video on any topic you can imagine. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then a video can be worth millions of words. So how do you take a video and turn it into something that can be submitted as an NPL document as part of an information disclosure statement? It needs to be converted into a PDF document as I will show below.

Checking Completeness of Art Citations with a Cited Art Matrix

In any patent case, it is important to make sure that all of the known art has been cited during prosecution across all of the patents in the portfolio. One tool that patent owners and lawyers can use to ensure that literature has been consistently and thoroughly cited across a patent family is an "art matrix." This post shows how to create an “art matrix” in Excel.

What Different Types of Art Must be Cited to the USPTO?

What are the types of information that need to be cataloged? Anything and everything. From the perspective of an Information Disclosure Statement filing, there three main types of “art”: U.S. Patent Documents, Foreign Patent Documents, and Non-Patent Literature. I will discuss what each of these categories includes and the citation of foreign language material.